Why Classical Schools Don’t Cancel Home

by Patience Griswold, Blogger and Social Media Specialist

In schools and Zoom classrooms across the U.S., curricula are being shifted away from old books and toward a smaller view of the world. In a recent opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal titled, “Even Homer Gets Mobbed” Meghan Cox Gourdon responds to a Massachusetts school’s decision to ban Homer’s Odyssey, writing,

Their ethos holds that children shouldn’t have to read stories written in anything other than the present-day vernacular… No author is valuable enough to spare… The subtle complexities of literature are being reduced to the crude clanking of “intersectional” power struggles.

Far from giving us a broader view of the world, if we ban authors from the past in order to avoid the discomfort caused by interacting with literature that does not share our modern sensibilities we truncates our understanding of the world around us by taking away the opportunity to see it from outside of our own particular moment in history. Literature offers us the opportunity to travel across time and space, and that travel often does make us uncomfortable. Travel has a tendency to do that. With a crick in our neck and a feeling of receiving a little more information than we can actually process in the moment we are brought into a new experience of the world, one that looks and feels different and forces us to see the idiosynchrosies of our own time and place. Only with reading, our sore neck and out-of-place-tourist feeling comes not from hours on an airplane, but from slipping between the pages of a book into a time and place that is different from our own.

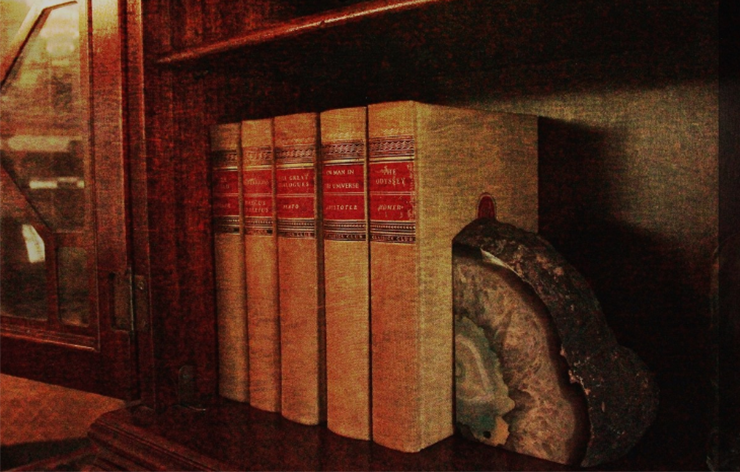

C.S. Lewis once wrote that, “Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books.” Old books force us out of our own culture and era and give us a fresh look at the world. My world is very different from Homer’s, and by entering into a time and place whose customs, values, traditions, and language are different from my own, I am able to see not only a “whole new world” but my own world more clearly. The great books of the classical tradition introduce us to our own culture. Far from reinforcing an echo chamber, they force us out of an echo chamber.

This is not all that old books do for us. By reading old books we learn to see not just the particulars of our experience, but the universals of the human experience. In old books we see different iterations of ideas that are around today, and in literature throughout the ages we see and feel universal elements of the human experience.

Maya Angelou once said that the first time she read Shakespeare’s 29th Sonnet, she assumed the writer must have been a black girl because of how well the words captured her own feelings as a black girl growing up in the segregated south. “And when Angelou recited them to us, these words sounded indeed like they had sprung forth from her soul,” wrote Karen Swallow Prior. “But Angelou’s message was that there is more in poetry—and, by extension, all art—that unites than divides us.” All good literature captures and puts into words the experiences that make us human—our hurts, our joys, and our need to be part of something greater than ourselves.

When Aeneas says, “Schooled in suffering, now I learn to comfort those who suffer too,” Virgil reminds us of how our grief and pain can prepare us to respond compassionately to others. Gilgamesh’s friendship with Enkidu and his visceral response to his friend’s death captures the universal need for connection and the overwhelming loss in the death of a loved one. In The Iliad, Homer warns us against the abuse of power when he says that, “A mighty king raging against an inferior is too strong.” The list could go on—in Faerie Queene we see a hero battle Despair and struggling in the fight until someone else reminds him of the truth, Augustine’s Confessions help us to remember God’s grace in our own lives by seeing His grace at work in Augustine’s life, Beowulf calls us to consider what makes a king good, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein pushes us to see the difference between what can be done and what should be done.

Classical schools teach great books from across the ages, rather than limiting themselves to books that were written for and by our modern era, because they draw us out of ourselves, challenging our assumptions, teaching us to recognize the ways in which we are all products of our culture, and inviting us into something greater. Through the great books we are reminded of universal human longings and experiences, enabling us to develop a deeper compassion for the people around us and a greater ability to understand and exercise wisdom toward the world around us.

Lewis’ novel Till We Have Faces challenges the reader to ponder the question: “How can [the gods] meet us face to face till we have faces?” It is an invitation to become truly us. As 2020 draws to an end, there is hope that the COVID masks that have brought out the worst in us will soon come off. But figuratively speaking, are we strong enough to live without the protective masks of other people’s ideas of who we ought to be? Till we have faces, our stories will remain untold.

Recent Posts

What Everyone Is Saying About Veritas

We want the best life for our child. A best life starts with a strong foundation. Veritas Academy is that foundation. We couldn’t be happier with our choice to choose Veritas.

Because of Veritas Academy’s commitment to students, my children are motivated to learn, they are challenged at their skill level instead of being held back due to their ages.

Transition from other educational models is seamlessly supported. Staff and teachers are proactive and caring to the smallest detail. Leadership goes above and beyond for ALL students.

Veritas Academy prepared my child for college. His biology professor said his papers are some of the best first-time college papers she has ever seen.